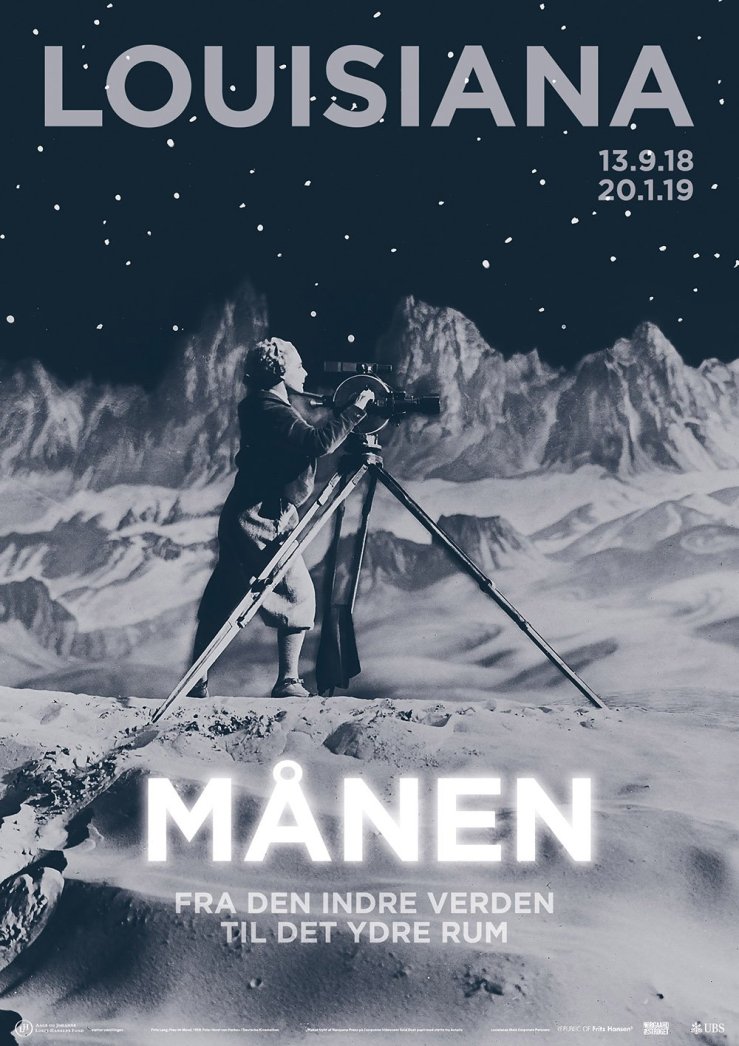

When life on earth seems all too crazy, there’s nothing like a trip to the moon to give you perspective. With the upcoming 50th anniversary of the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing, the lunar experience has never been so within reach. In cinemas there’s the awe-inspiring yet sobering Neil Armstrong biopic First Man, and/or have another excuse to visit Denmark and head to THE MOON: From Inner Worlds to Outer Space exhibition at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art.

A scenic train ride just north of Copenhagen, Louisiana is worth a visit for its dreamy setting alone: a sea-side villa overlooking the Oresund Strait – Sweden lies just across the water – and whose back garden features a fairy-tale lake. It’s a place of calm and escape.

stars around the beautiful moon

hide back their luminous form

whenever all full she shines

on the earth

silvery

– Sappho

Take the anonymous back entrance to The Moon exhibition (Louisiana’s not big on signs) and you start with moon-inspired poetry (the finest from Sappho, Borges, Leopardi, Dickinson and Plath) and end being serenaded by a ghostly unmanned grand piano playing – what else? – Mozart’s Moonlight Sonata.

The museum presents “a multifaceted portrait of the Moon and its significance in modern culture” and it’s brilliant. With its 6 themes – Moonlight, Selenography, The Moon of Myth, The Moon Landing, The Colonisation of Space and Deep Time – the exhibition is almost guaranteed to re-ignite curiosity in a satellite that humans have perhaps come to take for granted, not least since we stuck a flag on it.

Deep Time explores the geology of the earth and moon with a plethora of fascinating facts. It reminds us that while the moon is moving away from the earth, the earth’s rotation is slowing down. More of a surprise was that the earth is technically pear-shaped.

In The Colonisation of Space, various architectural designs are on display for inhabiting the moon, the most attractive of which is China’s 3D-printed igloo. According to the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, no government can lay claim to any celestial body, not that it has stopped anyone from trying. Nor does it seem to have prevented the 100+ million pieces of space junk orbiting our planet. The seductive voices of musician Gruff Rhys and actress Sally Potter narrate two trippy short films on the subject.

The earth looked like a jewel floating in blackness.”

Video art features heavily throughout the exhibition and offers some of the most memorable experiences. Towards the end/beginning of the exhibition, an astronaut describes both the beauty of space and the physical challenges of returning to earth – thwarted balance and acceleration, heightened sensitivities and the sheer weight of everything: “My wristwatch felt like a bowling ball.” Adapting to earth, it turns out, is even harder than adapting to space.

One way to avoid the massive come-down is to take a journey of a different kind and Louisiana offers that very thing. Artist Laurie Anderson’s virtual reality installation “To the Moon” is the absolute highlight of the exhibition. As if inhabiting a video-game, participants can walk on and float above the moon whilst extended arms allow for scrambling up craters. You have to trust where you are going for when you find yourself riding a donkey to the edge of a cosmic abyss or perched on the peak of a mountain, it’s a battle of the senses in order not to lose balance.

Both political and poetic, Anderson’s journey conjures feelings of wonder and loss. There is the sense of fragility of life on earth where images of dinosaurs and the word democracy become stardust. “I like stars,” Anderson says, “because we can’t harm them.”

The Moon Landing section offers stunning photographs by Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong as well as fascinating work by the artist Robert Rauschenberg who was invited by NASA to witness the launch of Apollo 11. Lithographs and collages produced for the unpublished Stoned Moon book capture the sublime imagination and the sheer enormity of the mission. The text in his collages offer an amusing and poetic take: “Fantastic things happen when destinies bump and interlock.” Artist Yves Klein, meanwhile, provides a healthy does of scepticism. Klein was against the superpowers’ space programmes. Space travel, he believed, should take the form of a spiritual journey.

Symbol of Longing

The Moon of Myth explores the role of the moon in our imaginations with stories from Danish folklore, surrealist art from Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst and Joseph Cornell and the world’s first sci-fi, Georges Méliès’ raucous hand-coloured A Trip to the Moon (1902) – a film that is very much out-there.

For the artists of Romanticism (the so-called “moon-light period” of 19th century European culture) the moon was a symbol of longing. “The sublime power of the moon lies in its distance from us: it is at once visible, accessible and yet at a distance and therefore unattainable.” In other words, the moon is the ultimate muse.

The Moonlight section features some gorgeous 19th century landscape paintings where “the frailty of human life is contrasted with the Moon’s eternal light.” It is somewhat ironic that artists were busy fetishising moonlight at a time when artificial light was fast taking over.

Moonlight nowadays has become an endangered species, an issue highlighted by Scottish artist Katie Paterson’s Light Bulb to Simulate Moonlight. It’s a work of art that does what it says on the tin – a single light bulb in a room. Outside, a set of 289 bulbs offer a lifetime’s supply of moonlight. After Laurie Anderson’s VR trip to the moon, the experience of sitting in a room with a single hanging light bulb was a tad underwhelming (but then I did the exhibition backwards). Paterson’s clinical work however encourages a renewed appreciation of the real thing.

Perhaps the most stunning images of the exhibition are NASA’S up close and personal photographs of the moon’s surface. Located in Selenography, this part of the exhibition tells the story of the mapping of the moon, an occupation that dates all the way back to Galileo in 1609, when, thanks to his improved telescope, he discovered that the surface of the moon was anything but perfect.

The NASA photographs are both beautiful and intriguing and include a shot of the mysterious dark side of the moon. Technically it’s not so dark (it’s officially called the far side of the moon) as the “dark side” receives just as much sunlight as its earth face.

A happy coincidence is the presence of the Yayoi Kusama installation, Gleaming Lights of the Souls. in the midst of THE MOON exhibition. In place since 2008, Gleaming Lights is a mirrored room full of tiny hanging lights that constantly change colour. With its 360° views of infinity, Gleaming Lights encourages a sense of wonder and embodies the spirit of THE MOON exhibition, a place where inner worlds and outer space collide.

First Man

For a blockbuster about space travel, First Man is surprisingly down-to-earth, subdued even. Director Damien Chazelle, whose previous films include La La Land and Whiplash, once again ventures behind the scenes of show business with a low-key biopic of Neil Armstrong, the man who fronted one of the 20th century’s greatest spectacles.

First Man is as much about one man’s grief as it is about stepping foot on the moon and the film plays on the lines between life and death. Devastated after the death of his young daughter, Armstrong remains the consummate professional, confident in his ability to get the job done. Humble, conscientious and tactiturn, Armstrong (Ryan Gosling) is a welcome antidote to the more usual bravado of the on-screen American hero.

First man doesn’t glamourise space travel. In fact it does quite the opposite. As with the early days of aviation (see Mary S Lovell’s biography of aviation pioneer Amelia Earhart) space travel was an uncomfortable and perilous endeavour where the slightest error could result in tragedy; it required high-intelligence and nerves of steel. Armstrong, of course, had both and thus narrowly avoids catastrophe on several occasions.

Not only does Armstrong lose his daughter to illness, he also loses friends and colleagues (who themselves leave families behind) in the name of the space race. First Man doesn’t offer a fixed view however it does question the point of space travel. There are scenes of protests claiming that the money would be better spent fixing problems on earth and that space travel is a white man’s game. Armstrong’s long-suffering and otherwise stoic wife Janet (Claire Foy) lets loose at one point in the film calling NASA “a bunch of boys making models out of balsa wood.”

Whilst politicians vie for prestige and scientists advocate for research, at a press conference, Armstrong is more circumspect: “Leaving the planet, and seeing how thin the atmosphere is that keeps us alive… seeing, with one’s own eyes, just how fragile human life is… gives a different perspective.”

That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

First Man culminates with Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin (shout out to Second Man) landing and walking on the moon. Not only does the film manage to convey the sheer enormity of the achievement, it maintains the suspense even though we know the mission was successful. And rather than highlighting the moon landing as an American achievement (the flag is shown but not the moment when the flag was placed), Chazelle focusses more on human endeavour.

For Armstrong the moon landing was deeply personal. In the film he takes a moment to himself where he walks to a nearby crater and leaves his daughter’s bracelet. (Whether or not Armstrong really left anything on the moon we may never know unless we go back, however he did stray from the official plan.) Moreover, that a man of so few words should come up with the quote of the century is remarkable.

I loved First Man. But it’s not really about going to the moon. It’s about a man so desperately sad that he‘d risk his life to go on a faraway rock where everything is dead, silent, and still forever. “Do you think I’m standing out here because I want to talk to somebody?” – Elena Lazic, film critic

First Man is a fitting tribute to a man of extraordinary courage and by extension, all astronauts and their families. Brilliantly acted – Ryan Gosling and Claire Foy are wonderful. My only gripe is that the formidable Janet Armstrong doesn’t get a role beyond being the long-suffering wife. A recent New York Times interview with the Armstrong sons revealed that Janet taught synchronised swimming. Further research reveals that she founded the El Lago Aquanauts in 1964, a team in which many astronaut families were involved. At the time of the Apollo 11 mission in 1969, the team were competing in the Nationals. Wouldn’t scenes of synchronised swimmers have contrasted beautifully with astronauts in space?

If there’s one thing I’ve learnt from THE MOON exhibition and First Man, it’s that, whilst space travel can take different forms, I never want to leave planet earth. And the moon? Best viewed from a distance.

Even a simple gesture such as flying both the Jamaican and Scottish flags above the plinth would be a welcome display of solidarity. It is no coincidence that the two flags are so similar in design. There is in fact a new lottery-funded project called

Even a simple gesture such as flying both the Jamaican and Scottish flags above the plinth would be a welcome display of solidarity. It is no coincidence that the two flags are so similar in design. There is in fact a new lottery-funded project called